VANCOUVER — At the previous Summit in Sydney, the OpenStack Foundation announced a new integration strategy to support open infrastructure. This strategy resulted in the definition of several focus areas and the Foundation launching its first non-OpenStack project, Kata Containers.

Speaking at the Vancouver Summit, the OSF’s VP of engineering Thierry Carrez took a deep dive into these changes and what they mean for the future. Here’s a summary of his 40-minute talk, you can catch the video here.

First, a bit of background. Back in 2017 a number of discussions in the community all pointed to a similar need for a change. OpenStack started as very project focused, “we equated the community that was producing software with the software being produced,” Carrez says. This was reinforced by the structural project reform in 2015, dubbed the big tent.

“It helped us grow to the massive size that we are today but it was pretty clear that we were hitting some of the limits of that model being project-centric,” he says. Those limitations include isolation from adjacent communities, adoption of other technologies and confusion about about the very definition of OpenStack. In addition, the success of OpenStack lead to requests from outfits like NASA seeking more open collaboration or companies interested in edge or container infrastructure but these projects didn’t fit into the big tent structure.

“What really struck a chord with me and signaled a need for change was realizing our users were mixing and matching open infrastructure technologies to solve their needs and how difficult that integration was,” he says.

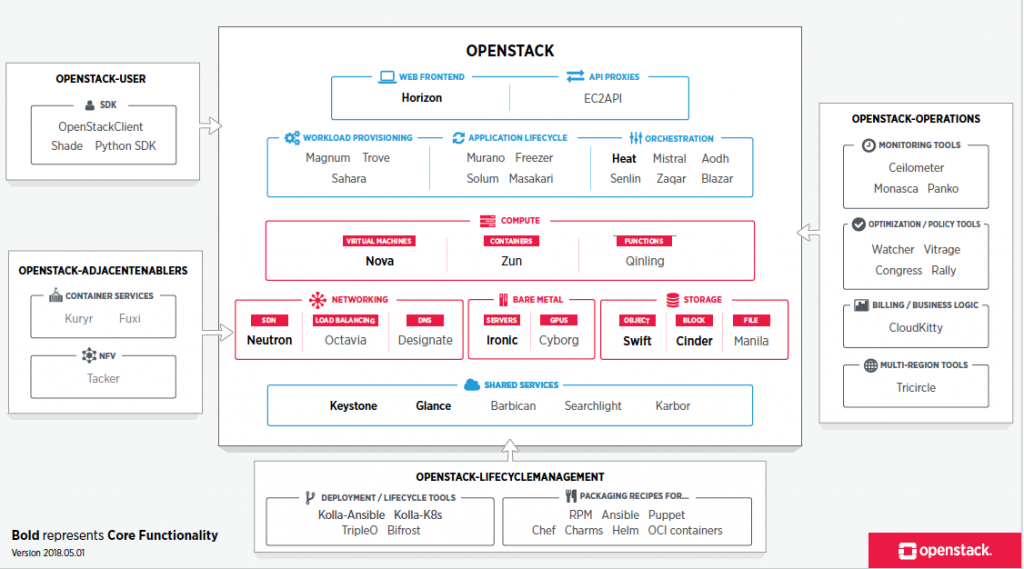

So when the board of directors, the Technical Committee, the User Committee and the OpenStack foundation staff met in March 2017 to define strategic issues to work on, better communication about what is OpenStack emerged as key. The result of that work is the OpenStack map.

The map shows what the community produces but focuses on a user perspective, highlighting the pieces of software that you might be interested in deploying to solve a specific problem, says Carrez.

The central piece is the OpenStack cloud infrastructure framework which has multiple components but all of them provide a service that will be consumed by cloud end users through APIs. On the right side are add-on tools to facilitate operations — monitoring, billing etc.— and on the left are bridges — like SDKs and libraries — that facilitate work with adjacent communities. “That lets us really target the various components that we produce to people who might be interested in deploying them,” he adds.

Shining a light on continuous integration

“One thing we did really well in OpenStack is building continuous integration in from day zero,” Carrez says. “The sad part is that this incredible system was invisible to other communities or other people on open-source projects because it was seen as OpenStack project infrastructure.” The fact that it’s extremely reusable got completely lost in a strategy that tended to promote the entire stack, he says. That’s where the launch of Zuul comes in as the second discrete project.

The approach gets back to the roots of OpenStack, a strong belief that in order to create really successful open-source technology, open source is not enough. It requires open collaboration, where any individual, any organization can contribute as an equal on a level playing field without anyone holding the keys to the kingdom.

Other core concepts include placing equal importance on upstream and downstream development and last, but not least, having fun. “We’re embarking on an ambitious journey and if we don’t have fun along the way we don’t create a community that’s really nice to be in.”

Community

OpenStack has always been more than the sum of its software: from the beginning it was a coalition of like-minded organizations, coming together around the concept of openly developing an open infrastructure solution. These companies might be competitors to public-cloud giants, retailers, telecoms who aren’t interested in “funding their own long-term extinction by financing Amazon AWS,” Carrez says, or research outfits like CERN with massive compute needs.

And while the OSF is expanding to house new initiatives, it’s a focused effort. “We are not interested in grabbing every interesting project out there,” says Carrez. “It’s not a land grab where anything goes. All projects need to be about open infrastructure and they need to play well together.”

Governance

Answering a question from the audience about the what the governance structure will be going forward, Carrez explains that there will continue to be single board of directors for the OSF. The other projects will potentially have their own technical bodies, but it depends on the focus area. Some are more synergistic with other projects and others are more standalone.

There will also always be some version of the User Committee, to make sure those voices are heard, but again how that mechanism works depends on the project. “For Zuul, we need to structure things in a way so the consumers of the project infrastructure can they can feed back into into the development team, but the I’m not sure we would call it a user committee.”

Catch his entire 40-minute talk below.

- Demystifying Confidential Containers with a Live Kata Containers Demo - July 13, 2023

- OpenInfra Summit Vancouver Recap: 50 things You Need to Know - June 16, 2023

- Congratulations to the 2023 Superuser Awards Winner: Bloomberg - June 13, 2023

)