It’s been a while since I talked about Ceilometer and its companions, so I thought I’d go ahead and write a bit about what’s going on this side of OpenStack. I’m not going to cover new features and fancy stuff today, but rather give a shallow overview of the new project processes we initiated.

Ceilometer is growing

Ceilometer has grown a lot since we started it three years ago. It has evolved from a system designed to fetch and store measurements, to a more complex system, with agents, alarms, events, databases, APIs, etc.

All those features were needed and asked for by users and operators, but let’s be honest, some of them should never have ended up in the Ceilometer code repository, especially not all at the same time.

The reality is we picked a pragmatic approach due to the rigidity of the OpenStack Technical Committee in regards to new projects to become OpenStack integrated – and, therefore, blessed – projects. Ceilometer was actually the first project to be incubated and then integrated. We had to go through the very first issues of that process.

Fortunately, now that time has passed, and all those constraints have been relaxed. To me, the OpenStack Foundation is turning into something that looks like the Apache Foundation, and there’s, therefore, no need to tie technical solutions to political issues.

Indeed, the Big Tent now allows much more flexibility to all of that. Back a year ago, we were afraid to bring Gnocchi into Ceilometer. Was the Technical Committee going to review the project? Was the project going to be in the scope of Ceilometer for the Technical Committee? Now we don’t have to ask ourselves those questions, now that we have that freedom, it empowers us to actually do what we think is good in term of technical design without worrying too much about political issues.

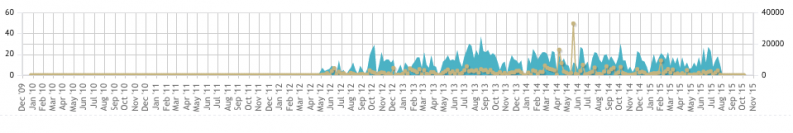

Ceilometer development activity

Acknowledging Gnocchi

The first step in this new process was to continue working on Gnocchi (a time series database and resource indexer designed to overcome historical Ceilometer storage issue) and to decide that it was not the right call to merge it into Ceilometer as some REST API v3, but that it was better to keep it standalone.

We managed to get traction to Gnocchi, getting a few contributors and users. We’re even seeing talks proposed to the next Tokyo Summit where people leverage Gnocchi, such as, "Service of predictive analytics on cost and performance in OpenStack," "Suveil" and "Cutting Edge NFV On OpenStack: Healing and Scaling Distributed Applications."

We are also doing some progress on pushing Gnocchi outside of the OpenStack community, as it can be a self-sufficient time series and resource database that can be used without any OpenStack interaction.

Branching Aodh

Rather than continuing to grow Ceilometer, during the last summit we all decided that it was time to reorganize and split Ceilometer into the different components it is made of, leveraging a more service-oriented architecture. The alarm subsystem of Ceilometer being mostly untied to the rest of Ceilometer, we decided it was the first and perfect candidate to do that. I personally engaged into doing the work and created a new repository with only the alarm code from Ceilometer, named Aodh.

Aodh is an Irish word meaning fire. A word picked so it also had some relation to Heat, and because we have some Irish influence around the project.

This made sense for a lot of reason. First because Aodh can now work completely standalone, using either Ceilometer or Gnocchi as a backend – or any new plugin you’d write. I love the idea that OpenStack projects can work standalone – like Swift does for example – without implying any other OpenStack component. I think it’s a proof of good design. Secondly, because it allows us to resonate on a smaller chunk of software – a reason really under-estimated today in OpenStack. I believe that the size of your software should match a certain ratio to the size of your team.

Aodh is, therefore, a new project under the OpenStack Telemetry program (or what remains of OpenStack programs now), alongside Ceilometer and Gnocchi, forked from the original Ceilometer alarm feature. We’ll deprecate the latter with the Liberty release, and we’ll remove it in the Mitaka release.

Lessons learned

Actually, moving that code out of Ceilometer (in the case of Aodh), or not merging it in (in the case of Gnocchi) had a few side effects that I admit I think we probably under-estimated back then.

Indeed, the code size of Gnocchi or Aodh ended up being much smaller than the entire Ceilometer project – Gnocchi is seven times smaller and Aodh five times smaller than Ceilometer – and therefore much more easy to manipulate and to hack on. That allowed us to merge dozens of patches in a few weeks, cleaning-up and enhancing a lot of small things in the code. Those tasks are very much harder in Ceilometer, due to the bigger size of the code base and the small size of our team. By having our small team working on smaller chunks of changes – even when it meant actually doing more reviews – greatly improved our general velocity and the number of bugs fixed and features implemented.

On the more sociological side, I think it gave the team the sensation of finally owning the project. Ceilometer was huge, and it was impossible for people to know every side of it. Now, it’s getting possible for people inside a team to cover a much larger portion of those smaller projects, which gives them a greater sense of ownership and caring. Which ends up being good for the project quality overall.

That also means that we technically decided to have different core teams by project (Ceilometer, Gnocchi, and Aodh) as they all serve different purposes and can all be used standalone or with each others. Meaning we could have contributors completely ignoring other projects.

All of that reminds me some discussion I heard about projects such as Glance, trying to fit new features in – some that are really orthogonal to the original purpose. It’s now clear to me that having different small components interacting together that can be completely owned and taken care of by a (small) team of contributors is the way to go. People that can therefore trust each other and easily bring new people in, makes a project incredibly more powerful. Having a project covering a too wide set of features make things more difficult if you don’t have enough manpower. This is clearly an issue that big projects inside OpenStack are facing now, such as Neutron or Nova.

This post first appeared on Julien Danjou’s blog, jd:/dev/blog. You can follow him on Twitter at @juldanjou. Superuser is always interested in how-tos and other contributions, get in touch at [email protected]

Cover Photo by Mohamed Somji // CC BY NC

- Ceilometer gets major performance boost - January 19, 2016

- Benchmarking Gnocchi for fun and profit - December 1, 2015

- Ceilometer, Gnocchi and Aodh: Liberty progress - August 6, 2015

)